Tattoo Removal Methods Used by Tattooists in the Late 1800s and Early 20th Century

Tattoos have been part of human history for thousands of years, used for personal expression, spiritual meaning, or as a form of punishment. Historical records, such as those from Herodotus, reveal that Persians tattooed slaves and prisoners of war, while the Greeks used tattoos to mark and punish criminals. These marks often carried stigma, serving as painful reminders of control or social exclusion.

For as long as tattoos have existed, people have searched for ways to remove them. Whether it was to erase forced markings, move past personal regrets, or adapt to changing social norms, tattoo removal methods have evolved over time. Advancements in medical knowledge and technology brought significant improvements, transforming what was once a crude and painful process into more refined approaches. From ancient practices to 19th- and 20th-century innovations, this article explores the fascinating history of tattoo removal and how it has developed alongside changes in medicine and society.

Ancient Tattoo Removal: A Journey Through Time

Tattoo removal has been on people’s minds for thousands of years. From spiritual interventions to early medical experiments, ancient societies had fascinating ways of erasing unwanted marks. Here’s a look at some of their techniques.

Healing Temples and Miraculous Tattoo Removal (5th Century BCE–2nd Century CE)

The Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus was famous for its miraculous healings. Pilgrims would come here seeking cures for all kinds of ailments, including tattoos. People slept in the sanctuary, hoping for divine intervention in their dreams. Some inscriptions (iamata) describe tattoos being transferred to bandages by the god Asclepius himself, leaving the skin clean. It’s an incredible example of how healing and spirituality were deeply connected in ancient Greece.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE)

The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote about plants with blistering properties in his book Naturalis Historia. One of these plants, Ranunculus (possibly called 'batrachion'), was believed to create burns or blisters when applied to the skin. This effect might have been used to remove tattoos or marks. While Pliny didn’t directly mention tattoo removal, his work gives us clues about how ancient remedies could be adapted for the purpose.

Dioscorides (40–90 CE)

In his famous text De Materia Medica, Dioscorides detailed countless plants and minerals used in ancient medicine. He didn’t specifically discuss tattoo removal, but his knowledge of caustic and medicinal substances shows how ancient practitioners could have approached skin treatments. His work laid the foundation for pharmacology and remains a key resource for understanding ancient medical practices.

Galen (129–216 CE)

Galen, one of antiquity’s greatest physicians, focused heavily on skin conditions. In works like De Remediis Parabilibus, he described treatments for various ailments. While tattoo removal isn’t explicitly mentioned, Galen’s emphasis on combining natural remedies with medical techniques suggests that he may have explored ways to deal with tattoos or scars.

Tattoo Removal Methods from Ancient Times to the 20th Century

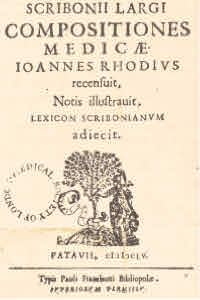

Scribonius Largus (1st Century CE)

Scribonius Largus, a Roman physician under Emperor Claudius, provided one of the earliest documented tattoo removal methods. In his work Compositiones Medicamentorum, Chapter 231, Scribonius detailed a caustic mixture intended to obscure tattoos (stigmata):

- Ingredients: Garlic, blister beetles (cantharides), sulfur, and chalcopyrite (copper ore), mixed with wax and oil.

- Procedure: The mixture was applied to the tattooed area, causing irritation and ulceration. Over time, a black discharge formed, and once healed, a scar would obscure the tattoo.

- Risks: This process was intensely painful, carried a high risk of infection, and left permanent scars.

Source: Scribonius Largus, Compositiones Medicamentorum, Chapter 231. Translation by Ianto Evans, available at University of Glasgow Theses, pp. 144–145.

The Compositiones Medicamentorum by Scribonius Largus was first printed in Rome in 1529 by Johannes Philippus de Lignamine.

The 1655 edition, published in Padua, is a later commentary and is currently housed in the Wellcome Institute Library.

Aëtius of Amida (6th Century CE)

Aëtius of Amida, a Byzantine physician and court physician to Emperor Justinian, provided some of the most detailed descriptions of tattooing and tattoo removal in antiquity. His Tetrabiblos outlines two distinct methods for breaking down tattoo pigments:

Chemical Approach with Nitre and Resin of Terebinth

- Ingredients: Nitre (potassium nitrate) and resin of terebinth (turpentine).

- Procedure: Applied to the tattooed skin to dissolve pigments embedded in the skin's layers. Over repeated applications, this treatment ulcerates the skin, causing pigment to separate and leave scars.

Combined Chemical and Mechanical Approach

- Ingredients: Lime, sodium carbonate, pepper, rue, and honey.

- Procedure: The skin was pricked with needles to open its surface. A caustic mixture was applied to irritate and dissolve pigments, with salt rubbed in to enhance the effect. The process was repeated daily, over an extended period, until the tattoo pigment was removed, leaving minimal scarring.

- Context: Tattoos were often used to mark individuals such as slaves or criminals in Byzantine society. Removal methods like those described by Aëtius were likely aimed at helping individuals obscure or erase these marks as part of reintegrating into society.

Centuries later, as global exploration expanded, tattooing and its removal continued to evolve, as seen in the accounts of Lionel Wafer.

Sources:

Aëtius of Amida, Tetrabiblos, Book 8, Chapter 12. Corpus Medicorum Graecorum, Vol. 8.2, ed. A. Olivieri (1950), pp. 417–418.

Jones, C. P. “Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.” Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 77, 1987, pp. 139–155.

Dinter, Martin, and Khoo, Astrid. Tattoos in Antiquity: Social Stigma and Cultural Reclamation. King’s College London.

17th-19th Century Tattoo Removal

Lionel Wafer (1699)

Lionel Wafer, a 17th-century surgeon, described tattooing among the Kuna people in A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America (1699). Wafer also attempted to remove a facial tattoo for his companion using scarification, which involved cutting and scraping the skin. Despite his efforts, the tattoo could not be entirely removed, leaving residual markings and scars. This account highlights early tattoo removal methods' painful and largely ineffective nature.

Source:

Wafer, Lionel. A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America. London: James Knapton, 1699. Archive.org (Page 349).

Attempt to Remove Tattoos Using Chlorine (1872

In 1872, an article in The British Medical Journal detailed an experimental method for tattoo removal involving the use of chlorine. This approach represented an early exploration into chemical tattoo removal during the 19th century.

Procedure:

The method involved applying a chlorine-based solution directly to the tattooed area. Chlorine, known for its bleaching and disinfectant properties, was believed to break down tattoo pigments embedded in the skin. While there is no detailed record of its precise preparation or application, the procedure likely involved repeated treatments.

Risks and Limitations:

Although the theory behind using chlorine showed promise, the practice came with significant risks. The corrosive nature of chlorine could cause irritation, burns, and damage to surrounding skin tissue. Additionally, the lack of antiseptics and sterile techniques during the time heightened the risk of infection, making the method both painful and hazardous.

Historical Context:

The use of chlorine in tattoo removal reflects the growing interest in chemical solutions during the 19th century, as medical practitioners sought alternatives to physical methods like scarification. While this experiment paved the way for later innovations, it ultimately proved too crude and harmful for widespread adoption.

Source:

The British Medical Journal, Vol. 1, No. 592 (May 4, 1872), p. 488.

Jean-Louis Alibert (1835)

Jean-Louis Alibert, a French dermatologist, introduced a caustic paste made of quicklime and soap to destroy tattooed tissue. While effective, the process often resulted in severe burns and extensive scarring, demonstrating the continued risks of tattoo removal.

Source: Alibert, Jean-Louis. Monographie des dermatoses. Paris: Béchet Jeune, 1835. Archive.org.

While dermatologists like Alibert sought chemical solutions, other unconventional methods, like the use of chlorine or even sole-skin, were explored.

Sailor Tattoo Removal Practices (1880)

In an 1880 article published in the British Medical Journal, a contributor identified as W.S. described an unconventional tattoo removal method allegedly used by sailors. This method involved binding a "fresh sole-skin" (the underside of a fish) to the tattooed area, with the application repeated as needed. Whether this technique was genuinely effective or simply a tale circulated among seafarers remains unknown. Its inclusion in the British Medical Journal, however, indicates that it was deemed noteworthy enough to warrant documentation, lending a degree of curiosity—and perhaps credibility—to the method, at least in the eyes of its contemporaries.

As tattoo removal entered the 20th century, innovators like Charles Burchett Davis began refining methods to address safety and efficacy.

20th Century: A Period of Innovation

Charles Burchett Davis and Tattoo Removal Kits

In the early 20th century, Charles Burchett Davis (C.B. Davis), a distinguished tattoo artist and brother of the acclaimed George Burchett, revolutionised tattoo removal by introducing his improved tattoo removal kits. These kits offered a systematic, commercially available solution less invasive than earlier methods. The C.B. Davis tattoo removal kit was based on a three-chemical method.

Davis’s contributions made tattoo removal more accessible and efficient for tattooists and clients.

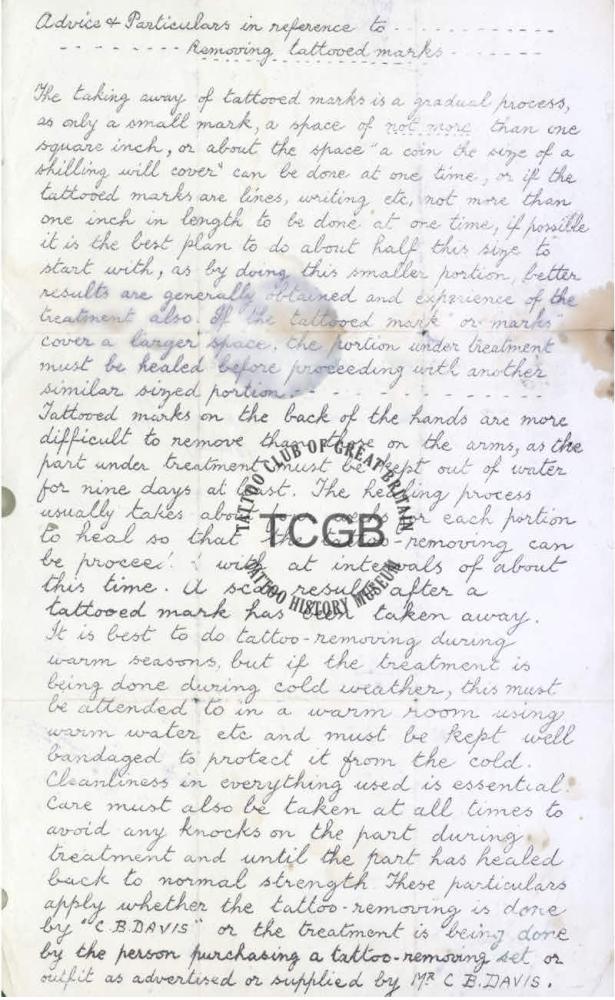

Charles Burchett Davis (C.B.Davis) Hand-written tattoo removal kit instruction.

Later printed instructions were used with the improved tattoo removal kit.

IMPORTANT

Please read the accompanying Leaflet very carefully before using the Set. ALSO, all three liquids must be kept away from, and not allowed to come into contact with, metal of any kind.

LIQUID No. 1 must never be placed on an open or blood wound, and great care must be exercised in cleanliness for everything used in connection with this treatment. Do not do more than a space, one inch square at any one time. After this has thoroughly healed, another similar portion could be done, but note remarks about LIQUID No. 1 before doing another portion near the part which has healed. Treatment may then continue until all tattooed marks have been taken out.

All knocks are dangerous, also the cold, so the part must be kept well bandaged. Keep the part cleansed about twice daily while there is an open wound, fresh ointment being applied on a clean bandage, the part being bandaged up again after being cleansed with water that has boiled and allowed to cool to a comfortable heat, using a good antiseptic soap. Liquids must be kept in a warm place and used in a warm room; cold air will weaken the applications.

After you have read, and fully understand the explanation sheet, the following are the instructions which must be carefully followed, as they are given from personal experience: First, wash the part to be treated and shave off any hair, being careful to avoid making any cut or scratch. Take LIQUID No. 1, and with a glass rod cover the tattoo mark with the liquid, making about three applications, letting each application dry before applying another, and remembering not to do more than approximately one square inch. After this has been done, and the flesh is dry, place LIQUID No. 1 away.

Now take LIQUID No. 2 and apply this in a similar manner over the part treated with the previous liquid (where the flesh should now be white, two or three applications as before). Let this remain for five to ten minutes, then, taking the scraper enclosed with the set, with the edge test the part to see whether the top layers of skin could be scraped away, or wait until you can do so without causing any pain. Then scrape off as much as you possibly can, but not to make the part bleed. Into the indentation you would have made, apply LIQUID No. 2, about three applications; the part will now be nearly black.

You now take LIQUID No. 3, make about four applications of this, taking care to fully cover the surface of the part with each application. Now cut off a portion of the special plaster, which must be slightly larger than the part it is to cover. Place the plaster over the part so that it will stick on the flesh, then bandage up, taking care not to bandage too tightly. After about three days the part will be slightly swollen, but there is no danger.

About the fifth day the part will begin to discharge; when the part has discharged for two days, take off the bandage and remove plaster. Kindly note that the plaster must not be taken off until the part is discharging. Wash the wound with water that has been boiled and allowed to cool to a comfortable heat, using a good antiseptic soap. After the part has been cleansed, if there remains any tattoo stain that cannot be washed out, apply LIQUID No. 2 and LIQUID No. 3 again (one or two applications according to the amount of tattoo left), place on a fresh portion of plaster, and bandage up again for a few more days. When the part has again been cleansed, and is seen to be free of all tattoo stain, you can now commence to heal the wound. Cleanse it twice daily as previously mentioned, place some healing ointment on a piece of clean bandage and then bandage up, continuing this until the part has quite healed. Should the bandage stick during the healing process, carefully bathe off to avoid breaking the new skin which is being formed. When the new skin has grown over the treated part it is advisable to keep this covered with the plaster until it has improved in strength.

When not in use, keep bottles airtight and away from extreme heat and cold.

CONTENTS OF THE IMPROVED TATTOO REMOVING OUTFIT

- Liquids Nos. 1, 2 & 3 (1 bottle each)

- 3 Glass Rods

- 1 Scraper

- 1 Pot Healing Ointment

- 1 Portion Medical Plaster

- 2 Bandages

- These Printed Instructions and an “Advice & Particulars” Leaflet, which you should read very carefully before using the set.

ADVICE and PARTICULARS LEAFLET REGARDING TATTOO REMOVING

The taking away of tattooed marks is a gradual process, as only a small mark, a space of not more than one square inch, or about the space "a coin, the size of a shilling will cover”, can be done at one time, or, if the tattooed marks are lines, writing, etc., not more than one inch in length to be done at one time. If possible, it is best to do about half this size to start with, as by doing this smaller portion, better results are generally obtained, and experience of the treatment also.

If the tattooed marks or mark cover a larger space, the portion under treatment must be healed before proceeding with another similar sized portion.

Tattooed marks on the back of the hands are more difficult to remove than those on the arms, as the part under treatment must be kept out of water for at least nine days. The healing process usually takes about four weeks for each portion to heal, so that the tattoo- removing can be proceeded with at intervals of about this time.

A scar generally results after a tattooed mark has been taken away.

It is best to do tattoo-removing during the warm seasons, but if the treatment is being done during cold weather, this must be carried out in a warm room, using warm water, etc., and the part must be kept well bandaged to protect it from the cold.

Cleanliness in everything used, is essential. Care must be taken at all times to avoid any knocks on the part during treatment, and until the part has healed back to normal strength.

Treatment must not commence if there is any wound, cut or graze (however slight) on the flesh where the tattooed mark is to be removed.

Persons with skin disease, impure blood or run-down in health, use this treatment at their own risk.

Ronald W. B. Scutt’s Research and Practice

Ronald W. B. Scutt, a dermatologist, surgeon, and author of Skin Deep (1974), worked closely with tattooists to improve tattoo removal techniques. As part of his research, Scutt visited Joe Cleverley and Ron Ackers at their renowned tattoo studio on The Hard in Portsmouth. He frequently spoke with them to gather insights for his book.

Joe and Ron shared their knowledge of the tannic acid and silver nitrate (caustic pencil) method, which tattoo artists already used at that time. Inspired by their discussions, Scutt purchased a tattoo machine from Ackers and began experimenting with the technique himself.

The Process: Tannic acid was tattooed into the skin, followed by the application of silver nitrate. The interaction between the two chemicals created a scab that, as it healed, expelled the tattoo pigment. It is unclear which variation of this method Scutt experimented with, as some tattooists mixed tannic acid with glycerine, and some also added hydrogen peroxide to the process.

Historical Context: This technique had been previously documented by Dr. Marvin Shie in 1928, who highlighted the risks of scarring and infection. Scutt refined this method, adding medical expertise and modifications.

Ronald W. B. Scutt and the Variot Method

In his 1972 article The Chemical Removal of Tattoos, Surgeon Captain Ronald W. B. Scutt revisited and refined the Variot method, developed initially in 1888. This method also involved tattooing tannic acid into the skin and rubbing silver nitrate over the treated area. Scutt’s modifications included using local anaesthetics and sterilised equipment, improving patient comfort and reducing complications.

Scutt’s work stands out for bridging traditional tattooist techniques with medical advancements, emphasizing safety and efficiency.

Legacy of Scutt’s Work: Scutt’s research marked a pivotal step in the historical progression of tattoo removal techniques. While the tannic acid and silver nitrate method is no longer used today, his work underscores the interplay between traditional tattoo removal practices and modern medical innovation.

Sources:

Scutt, Ronald W. B. The Chemical Removal of Tattoos. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 1972, S0007-1226(72)80043-2.

Shie, MD. A Study of Tattooing and Methods of Its Removal. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1928;90(2):94–99.

Additional Tattoo Removal Methods of the 20th Century

As tattoo removal methods continued evolving, various techniques emerged in the early 20th century. These methods provided further options for individuals seeking to remove tattoos, combining chemical, mechanical, and natural elements. Some innovations were based on earlier practices; others were new dermatology and body modification developments.

Tattoo Removal Methods of the Early 20th Century

As tattoo removal continued to evolve in the early 20th century, various chemical and mechanical methods emerged, many of which were experimental and often painful. These methods aimed to address the desire to erase unwanted tattoos, either due to personal regret or societal pressures. Here are some of the notable techniques from that era:

Salicylic Acid Method

The salicylic acid method used the exfoliating power of this common chemical to peel away layers of skin. A paste made by mixing salicylic acid with glycerin created a dough-like consistency. The paste was applied to the tattooed area and covered with a compress and plaster for five to seven days. When the dressing was removed, the outer skin layers containing the tattoo ink were scraped away. If any pigment remained, the process was repeated, sometimes requiring two or three applications. While relatively simple, this method required careful aftercare to avoid infection and the risk of deeper scarring.

-

Procedure: A paste of salicylic acid and glycerin was applied, covered, and left for five to seven days. The softened skin layers containing tattoo pigment were scraped away. If any pigment remained, the process was repeated, sometimes requiring two or three applications. While relatively simple, this method required careful aftercare to avoid infection and the risk of deeper scarring.

Papain Method

Papain, an enzyme derived from the papaya plant, is known for its ability to break down proteins. In this method, the skin was cleaned, shaved, and numbed before a solution of glycerol and papain was applied and worked into the skin using fine needles. The area was then dressed with antiseptic-soaked gauze and sealed with adhesive plaster for three days. Afterwards, a scab would form, eventually lifting away the tattoo pigment. Multiple treatments were often necessary for complete removal.

- Procedure: Glycerol of papain was tattooed into the skin. The area was dressed for three days. A scab formed, lifting the tattoo pigment as it healed.

- Sources: American Druggist (1920), papain formula included.

Tannin and Silver-Nitrate Method

The tannin and silver nitrate method combined two powerful chemicals to remove tattoos. A concentrated solution of tannin was applied to the tattooed skin and worked in using fine needles. Then, silver nitrate (often in stick form) was rubbed into the area. The reaction between tannin and silver nitrate formed a blackened scab that eventually fell off, leaving behind a scar that was said to be barely visible after healing. This method, while effective, required several weeks for the scab to form and heal.

- Procedure: Tannin was tattooed into the skin, followed by silver nitrate. A scab formed due to the chemical reaction, which fell off in two weeks.

- Result: Left a faint scar.

Nitric Acid Method

This method used the caustic properties of nitric acid and involved carefully applying the acid to the tattooed area. The treated skin would crust over, indicating the acid had reached the dermis. After washing the area with cold water, a scab formed, expelling the tattoo pigment as it healed. The procedure was effective, but it carried a high risk of scarring and required careful aftercare, including poultices and ointments to treat the inflamed skin.

- Procedure: Nitric acid was applied to the tattoo, causing the skin to crust over. After a scab formed and fell off, the tattoo faded.

- Aftercare: Warm poultices and carbolic oil treated inflammation.

Glycerol of Papain Metho

A more refined version of the papain method, the glycerol of papain solution was formulated as follows:

- Papain: 1 oz

- Hydrochloric acid: 40 mm

- Purified talc: 120 gr

- Glycerin: 8 oz

- Water: To make 16 oz

- Procedure. This mixture was applied to the tattooed area and worked into the skin using fine needles. After a dressing soaked in glycerol of papain was applied for three days, the area was covered with adhesive plaster until the scab formed. The scab, containing the tattoo pigment, would eventually fall off. This method was effective for smaller tattoos but required multiple sessions for larger ones.

Caustic-Potash Method

- Procedure: The caustic-potash method uses potassium hydroxide (caustic potash) to dissolve tattooed skin chemically. The area is washed with dilute acetic acid. Then, caustic potash is applied and left on for 30 minutes. The area is neutralized with hydrochloric acid before repeating the process daily. While effective over time, this method is slow and could cause significant skin damage if not carefully managed.

Building on chemical approaches, some methods combined these substances with mechanical techniques, as seen in the tannic acid and silver nitrate process.

Risks: Slow process and risk of skin damage.

Tannic Acid and Glycerin Method Used by Tattoo Artist

A mixture of tannic acid (with astringent properties) and glycerin (a moisturizing agent) was tattooed into the skin directly over the tattoo to be removed. The tannic acid chemically interacted with the ink, helping to break it down and lighten the pigment, while the glycerin reduced excessive dryness and irritation from the subsequent steps.

Caustic Pencil (Silver Nitrate)

After applying the tannic acid and glycerin mixture, a caustic pencil containing silver nitrate was used to rub the treated area. Silver nitrate’s corrosive properties created a chemical burn, targeting and breaking down tattoo pigment. This caused the skin to turn black and form a scab.

Chessboard Technique

To minimize scarring and maximize effectiveness, only small, targeted areas were treated at a time, following the "chessboard method." Small sections, about one square inch or smaller, were treated, leaving gaps between treated areas. This allowed the skin to heal and reduced the risk of severe damage from the harsh chemicals.

Healing and Removal

After a week, the treated area would scab over and eventually fall off, removing some of the tattoo pigment. Since the process was limited to small areas per session, it required multiple treatments, allowing the skin time to heal between sessions.

Risks and Limitations

The caustic properties of silver nitrate made the procedure extremely painful and prone to complications such as scarring and infection. Over-treating large areas at once increased the risk of septic wounds and permanent skin damage. Additionally, the results were inconsistent, depending on the tattoo’s depth and the individual’s healing ability.

Legal and Health Concerns

This method, while once popular, became obsolete after the introduction of the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations (COSHH) in the UK in 2002. These regulations restricted the use of hazardous chemicals like silver nitrate in tattoo removal, prioritizing safety for both practitioners and clients. This shift marked the decline of chemical-based tattoo removal methods and paved the way for safer alternatives.

Conclusion

The tannic acid, glycerin, and silver nitrate method played a significant role in the history of tattoo removal. While it was effective in certain cases, it came with some drawbacks, such as the potential for scarring or uneven results. With the implementation of COSHH regulations and the advent of modern laser removal techniques, this method gradually fell out of use, replaced by safer and more reliable solutions.

Why People Removed Tattoos

Tattoo removal has never been merely about erasing ink; it often reflects deeper societal dynamics. In ancient Rome, tattoos were used to mark criminals and slaves, making removal a means of reclaiming dignity and reintegration into society.

By the 20th century, tattoo removal became a practical service for individuals such as sailors and soldiers. Prison tattoos were also a mark many sought to remove, often done under pressure or as a result of boredom in confined environments. These tattoos frequently became unwanted reminders of past experiences. Innovators like C.B. Davis recognized the need for an effective method to remove tattoos. Later, Scutt encountered a similar demand, particularly from sailors who regretted tattoos acquired while serving overseas. Scutt refined these techniques, making tattoo removal safer and more accessible. This allowed clients to adapt their appearance to changing personal and social expectations.

Conclusion

The history of tattoo removal reflects humanity’s enduring desire to modify body markings to align with personal identity and societal norms. From caustic ancient methods to the chemical innovations of Charles Burchett Davis and Ronald W. B. Scutt, tattoo removal has undergone a remarkable transformation.

While early techniques often caused significant pain and scarring, they paved the way for modern, minimally invasive approaches like laser treatments.

Disclaimer:

This article is for historical and research purposes only. While historical methods of tattoo removal may have been used in the past, they are no longer considered safe or effective. Always consult a licensed professional for modern tattoo removal options.

Historical Sources:

Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus (Attalus.org)

Pilgrims sought miraculous healings, including tattoo removal, through divine intervention at the Sanctuary of Asclepius in Epidaurus.

Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia. Perseus Tufts

Pliny discusses plants like Ranunculus, which were believed to aid in tattoo removal through their blistering properties.

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica. Wikipedia

Dioscorides compiles medicinal knowledge, offering insights into substances potentially used for tattoo removal.

Galen’s Contributions to Dermatology

Galen’s writings include treatments for skin conditions, which may have encompassed tattoo removal techniques.

Penn Museum

Scribonius Largus. Compositiones Medicamentorum, Chapter 231.

Translation by Ianto Evans, University of Glasgow Theses (pp. 144–145).

Aëtius of Amida. Tetrabiblos, Book 8, Chapter 12.

Corpus Medicorum Graecorum, Vol. 8.2, ed. A. Olivieri (1950), pp. 417–418.

German website. The book text is in Greek.

Wafer, Lionel. A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America.

A new voyage and description of the Isthmus of America.

A new voyage and description of the Isthmus of America.

London: James Knapton, 1699. Archive.org (Page 349).

Attempt to Remove Tattoo Marks Using Chlorine.

The British Medical Journal. Vol. 1, No. 592, May 4, 1872, p. 488. (JSTOR)

Jean-Louis Alibert (1835).

Monographie des dermatoses. Paris: Béchet Jeune, 1835.

Tattoo removal using "fresh sole-skin" bound on the mark.

British Medical Journal, May 8th, 1880, P.721. (JSTOR)

Modern Analysis and Commentaries:

Jones, C. P. “Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.”

Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 77, 1987, pp. 139–155. (JSTOR)

Dinter, Martin, and Khoo, Astrid. Tattoos in Antiquity.

Social Stigma and Cultural Reclamation. King’s College London.

Scutt, Ronald W. B. "Tattoo Removal Techniques."

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 1972, S0007-1226(72)80043-2.

AMERICAN DRUGGIST November 1920.

American Druggist tattoo Removal methods, November 1920.

Shie MD. A Study of Tattooing and Methods of Its Removal.

Journal of the American Medical Association, 1928;90(2):94–99.

Please note that access to some articles, such as those on JSTOR, may require a subscription or institutional access.