The Life, Legacy, and Mysteries of Prince Giolo: The Painted Prince of Southeast Asia

The story of Prince Giolo (Jeoly) intertwines intrigue, tragedy, and exploitation, serving as a vivid reflection of the colonial era's fascination with the exotic and the darker realities of human commodification. From his origins on the island of Miangas in Southeast Asia to his brief time in England as a public curiosity, Giolo's life provides a unique lens into 17th-century exploration, culture, and power dynamics. This article delves into every known facet of Giolo's life, death, and legacy, piecing together details to form a comprehensive narrative.

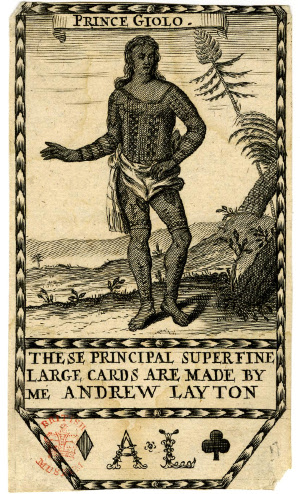

Image courtesy of: Tattooed Philippinne prince, Giolo, etching by John Savage, ca. 1692, State Library of New South Wales

Prince Giolo son to King of Moangis or Gitolo: lying under the Equator in the Long of 152 Deg 30 Min a fruitfull fland abounding with rich spices and other valuable commodities. This famous painted prince is the just wonder of the age, his whole body except hands, face and feet is curiously and most exquisitely Painted or stained full of variety and Invention with prodigious Art and Skill performed In so much in the ancient and noble Mistery of Painting or Staining upon Humane Bodies seems to be comprised in this one statily Piece. The Puctures & those other engraven Figures copied from him is now dispersed abroad serve only to deseribe as much as they can if sore-part of this intimitable Piece of Workmanship: The more admirable Back-parts afford us a Representation of one quarter part of the sphere upon & betwixt his shoulder whereid Arctick & Tropick Circle centre in S North Pole of his neck. And all ye other Lines Circles a Characters are done in such exact Symmetry & Proportioin, that it is astonishing & surmounts all ye has hither to be seen of this kind The Paint it self is so durable if nothing can wash it of or deface ye beauty of it. is prepared from the Juice of a certain herb or plant, peculiar to that country. wich they efteem infallible to preserve human Bodies from ye deadly poison or hurt of any venomous creature whatsoever an none but those of Royal Family are permitted to be thus painted with it. This excellent Piece has been lately seen by many persons of high quality a accurately surveyed by several learned Virtuosi an ingenious Travellers who have expressed very great satisfaction in seeing of it. This admirable person is about y age of 30, graceful and well proportioned in all his Limbs, extremely modest a civil, neat & cleanly, but his Language is not understood, neither can he speak English.

Name and Spelling

Dampier’s Writings: William Dampier generally referred to him as “Jeoly.”

Other Variants: Giolo, Gioli, Jeoly, and occasionally “Prince Giolo” or “Prince Giolo of Moangis/Gilolo.”

Because Dampier’s original texts are among the primary sources, “Jeoly” is the most common historical spelling. Modern authors sometimes use Giolo (or Gioli) based on 17th-century pamphlets and etchings that advertised him.

A Crafted Tale to Promote Prince Giolo

"An Account of the Famous Prince Giolo, Son of the King of Gilolo, Now in England with an Account of His Life, Parentage, and His Strange and Wonderful Adventures, the Manner of His Being Brought to England: With a Description of the Island of Gilolo, and the Adjacent Isle of Celebes, Their Religion and Manners" (1692) presents a richly detailed narrative that elevates Prince Giolo as an exotic and noble figure within 17th-century England. This publication meticulously constructs an elaborate backstory that intertwines royal lineage, dramatic adventures, and complex religious cosmologies, aligning with contemporary European audiences' fascination with the "exotic" and the "unknown."

Why Giolo’s Story Was Invented

During the 17th century, Europe was enthralled by accounts of distant lands and their inhabitants. Publications often featured exotic personalities to captivate public interest, blending fact and fiction to create compelling narratives. Prince Giolo, with his distinctive body ornaments and royal heritage, fits the archetype of a "living curiosity" meant to entertain and fascinate English society. The publication serves not only as a documentary but also as a marketing tool, presenting Giolo as a figure of nobility, tragedy, and heroism.

Clues That the Story Was Fiction

The detailed descriptions of Gilolo and Celebes, including their religious beliefs, political structures, and cultural practices, suggest a level of inventiveness beyond typical first-hand accounts. The intricate cosmologies involving angels, devils, and prophetic figures indicate a constructed mythology designed to intrigue readers. For instance, the account describes battles between good and evil forces, adding a layer of mystique and complexity that enhances Giolo’s portrayal as a heroic figure.

Giolo's narrative is replete with heroic feats, such as rescuing a princess, battling pirates, and enduring ordeals that border on the mythological. These elements are characteristic of romantic adventure tales rather than straightforward historical accounts. The inclusion of supernatural battles and elaborate rituals aligns with storytelling aimed at creating a mystical aura around Giolo’s persona.

The publication is presented as Giolo’s own account, claiming to be "written from his own mouth." This approach is a common literary device used in pamphlets and early novels of the period to lend authenticity and credibility to the narrative. However, the absence of identifiable authorship suggests that the story was likely crafted by publishers or promoters aiming to capitalize on Prince Giolo’s exotic appeal.

Origins: The Island of Miangas

Prince Giolo was said to have come from Miangas, a small island in the Talaud Islands near Mindanao, Philippines. Historically referred to as Moangis or Gilolo, Miangas was home to indigenous communities with rich traditions, including the art of tattooing. Tattoos in this region were deeply symbolic, representing social status, achievements, and spiritual protection.

When Giolo was brought to England, he was introduced as the "Son of the King of Moangis or Gilolo." This claim, likely fabricated or exaggerated, helped market him as an exotic curiosity to English audiences. The association with royalty added an air of mystique and intrigue to his exhibitions.

Indigenous Tattooing: A Cultural Legacy

Tattooing was an essential cultural practice in Southeast Asia during Giolo's time, particularly in the Philippines and neighbouring islands like Miangas. Tattoos were not merely decorative; they held profound cultural significance and were often earned through acts of bravery or spiritual rites.

1. Hand-Tapping Method

This was one of the most widespread techniques in ancient Filipino tattooing, especially for more intricate designs. It would have likely been used to create Prince Giolo’s elaborate tattoos.

- Process: A sharp tool, possibly made from metal, bone, or bamboo, would have been attached to the end of a wooden stick. The tattoo artist would then repeatedly tap the tool into the skin, depositing ink with each tap.

- Ink: The ink would have been made from soot or charcoal mixed with water, producing dark marks on the skin.

- Design: This technique allowed for the creation of detailed patterns and designs, which were common in tattoos that marked a person of status or distinction.

Technique:

- The tattooist employed a "hand-tapping" method, striking the back of the needle to embed the ink.

- This process was slow and painful, underscoring the recipient's fortitude.

2. Hand-Poking Method

Alternatively, the hand-poking method might have been used, especially for more straightforward or smaller tattoos. This method involved using a sharp object, like a thorn or a needle, to poke the skin repeatedly in a specific pattern.

- Process: Similar to hand-tapping, the artist would tap or press the sharp tool into the skin, and the ink would be deposited as the tool penetrated the skin.

- Ink: The same soot or plant-based ink could have been used here.

3. Cutting or Pricking the Skin

Given the prominence of the tattoos as a symbol of status, there’s a possibility that the cutting or pricking method was also used for some of Prince Giolo’s tattoos.

- Process: This method involved making small incisions or pricks in the skin, after which pigment was rubbed into the wounds. This could have left permanent scarring, making the tattoos even more pronounced.

- Significance: This method may have been used for tattoos that had a deeper spiritual or protective significance, as the scarring would emphasize the permanence and power of the marks.

4. Tools

The tools used to create Prince Giolo’s tattoos would have been crafted from locally available materials. These could include:

- Sharp objects: Metal, bone, or bamboo might have been used for the sharp points that punctured or tapped into the skin.

- Wooden or Bone Handles: These materials would have created a sturdy grip for the tattoo artist.

- Inks: Soot, charcoal, or plant-based pigments would have been used to create the tattoo ink, which would be applied in the tapping, poking, or cutting processes.

5. Cultural and Spiritual Meaning

Prince Giolo’s tattoos were likely not just decorative but had deep cultural and spiritual significance. Tattoos in the Philippines were often associated with achievements, warrior status, protection, and social rank. For someone like Prince Giolo, his tattoos could have symbolized his leadership, strength, and noble status. The process itself may have been ceremonial and connected to rites of passage or symbolic of his role in his community.

The methods used to create Prince Giolo’s tattoos would have followed traditional Filipino techniques, most likely incorporating hand-tapping or hand-poking, with possible cutting and pricking methods for added significance. The tattoos would have served as a powerful symbol of his identity, status, and the deep cultural traditions of the people of Miangas.

Significance:

- Tattoos represented milestones, spiritual beliefs, and social status.

- Warriors often adorned themselves with tattoos to signify victories in battle or rites of passage.

For Giolo, these tattoos were a vital part of his cultural identity. However, to the English public, his tattoos were a source of fascination and mystery. They were falsely promoted as having mystical powers, including protection against venomous creatures.

Encounter with William Dampier and Capture

Giolo’s life changed irrevocably around 1690 when he was captured by slave traders in Southeast Asia. He was sold to William Dampier, an English explorer, privateer, and chronicler. Dampier initially hoped that Giolo’s knowledge of local reserves of spices and gold might yield significant profits, but Jeoly failed to deliver on these expectations. Instead, Dampier turned to showcasing Giolo as a living curiosity. Returning to London in 1691, Dampier wrote, “I was no sooner arrived in the Thames, but [Jeoly] was sent ashore to be seen by some eminent persons; and I being in want of Money, was prevailed upon to sell … my share in him.” This transaction highlights the financial strain Dampier faced and his decision to exploit Giolo for public exhibitions.

Dampier transported Giolo to England in 1691, during the later stages of his first circumnavigation of the globe (1679–1691). This voyage, which included privateering, exploration, and trade, spanned multiple continents and years, with stops in the Caribbean, Pacific, and Southeast Asia.

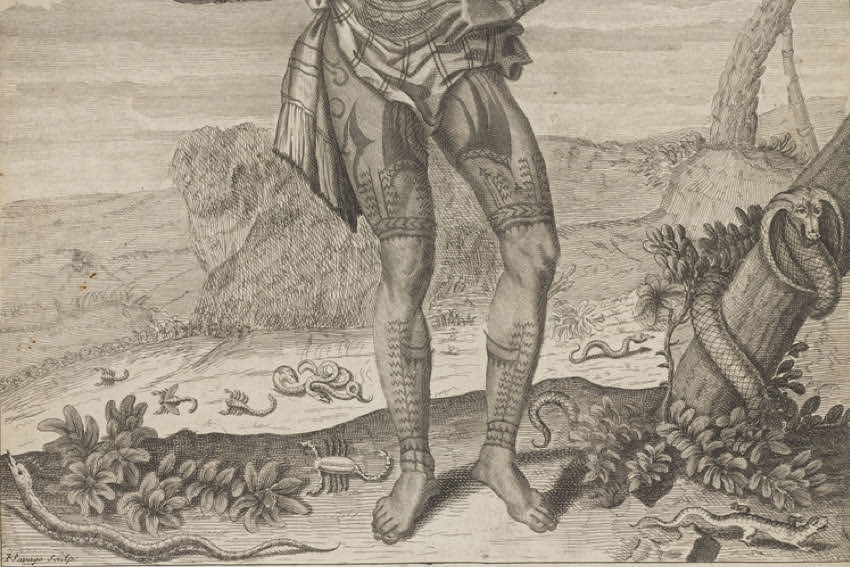

© The Trustees of the British Museum circa:1683-1700

Arrival in England and Public Exhibition

Giolo was commissioned to promote this “Just wonder of the Age,” with advertisements and exhibitions carefully crafted to emphasize his alleged royal lineage and the mystical qualities of his tattoos. In an engraving by John Savage, Giolo is posed like a typical European gentleman, with his striking tattoos—described as “full of variety and Invention with prodigious Art and Skill”—taking center stage. Promotional materials even claimed his tattoos had the power to repel snakes, an idea reinforced by depictions of snakes fleeing his presence in prints.

Promotional Materials:

- Etching by John Savage: This famous illustration depicted Giolo standing with his intricate tattoos on display. The inscription beneath the image proclaimed him the "Son to ye King of Moangis or Gilolo."

- Playbills and Pamphlets: Advertisements, including "An Account of the Famous Prince Giolo," detailed his supposed royal lineage and the mystical properties of his tattoos, which were falsely claimed to protect him from venomous creatures.

These materials sensationalized Giolo's origins and appearance, drawing large crowds eager to pay for a glimpse of the "Painted Prince."

Illness and Death in Oxford

Giolo’s time in England was tragically short. In 1692, he contracted smallpox, a deadly and highly contagious disease, while in Oxford. He succumbed to the illness, marking the end of his brief and exploited life in Europe.

Burial in Central Oxford

The burial site of Prince Giolo in Oxford remains a mystery due to the lack of definitive records. However, historians have identified two likely locations where he may have been interred after his death:

- St. Ebbe’s Churchyard: This central burial ground was commonly used for residents and visitors to the city during the 17th century. St. Ebbe’s proximity to where Giolo died makes it a plausible location for his burial. However, Giolo’s name does not appear in surviving parish records, which often omitted entries for marginalized individuals.

- St. Peter-le-Bailey Churchyard (Bonn Square): Another likely burial site is St. Peter-le-Bailey Churchyard, located near what is now Bonn Square. The original church was demolished in 1874, and the churchyard underwent significant redevelopment. Surviving burial registers from St. Peter-le-Bailey date back to 1585 but do not include Giolo’s name, suggesting he may have been buried anonymously.

Unmarked graves were common for marginalized individuals or outsiders during this period. Giolo’s burial in an unmarked grave aligns with the colonial-era treatment of individuals brought to England as curiosities. Redevelopment of these churchyards over the centuries has made locating his grave nearly impossible.

Legacy and Loss

After Giolo’s death, a fragment of his tattooed skin was preserved as an anatomical curiosity and displayed at Oxford University, where it was listed in the Musceum Pointerianum by John Pointer, an Oxford surgeon. Pointer included an item called "A bit of an Indian Prince's Painted Skin," alongside a famous 1692 engraving of Giolo in his preserved state. The skin was kept in two chests donated to St. John’s College Library in 1740, forming part of an anatomical collection. However, by the early 20th century, many of the items in Pointer’s collection, including Giolo’s painted skin, were lost or deteriorated. Today, the only surviving artifacts related to Giolo are the etchings and promotional materials created during his exhibitions, housed in collections such as The British Museum (etchings by John Savage) and The State Library of New South Wales (pamphlets and illustrations).

In recent years, artists and scholars have revisited Giolo’s story, exploring themes of colonial exploitation, identity, and cultural heritage. Filipino artist Pio Abad created works inspired by Giolo, including reimagined engravings of his tattooed hand, emphasizing the humanity behind his tragic narrative. The transformation of Giolo’s body into an object of scientific fascination reflects the way indigenous individuals were often treated as curiosities, stripped of their identities and reduced to specimens for European study, rather than being remembered as individuals with their own stories. The surviving engraving of Giolo offers a lasting reminder of this dehumanizing treatment, while modern reflections continue to reconsider the implications of his legacy and loss.

After Giolo’s death, a fragment of his tattooed skin was preserved as an anatomical curiosity and displayed at Oxford University. However, this specimen was lost by the early 20th century. Today, the only surviving artifacts related to Giolo are the etchings and promotional materials created during his exhibitions, housed in collections such as:

The Voyage of William Dampier

Giolo’s story is inseparable from the voyages of William Dampier, one of history’s most renowned explorers. Dampier’s first circumnavigation (1679–1691) was a continuous expedition involving privateering, trade, and exploration. His detailed observations, later published in A New Voyage Round the World (1697), became influential in the fields of geography and natural history.

However, Dampier’s treatment of Giolo reflects the exploitative nature of colonial-era expeditions, where individuals were dehumanized and commodified for profit.

Conclusion: Remembering Prince Giolo

Prince Giolo’s life is a story of resilience and tragedy. His tattoos, celebrated as exotic curiosities in England, symbolized the rich cultural traditions of his homeland. Yet, his capture, exploitation, and premature death underscore the human cost of colonialism and the erasure of indigenous identities.

While much of Giolo’s life remains shrouded in mystery, his legacy persists as a reminder of the complexities of cultural encounters during the Age of Exploration. By revisiting his story, we honor not only his life but also the vibrant heritage he represented.

References

- A New Voyage Round the World - William Dampier

- Esquire article on Jeoly

- Curiosity, Wonder, and William Dampier's Painted Prince - Geraldine Barnes

- UCL Museums blog

- An Account of the Famous Prince Giolo Son of King of Gilolo, Hyde Thomas 1692

- University of Michigan Library

- Early English Books 1641 - 1700

Jeoly’s Exhibition: Was the Inn Called the Blew Boar’s Head Inn?

In June 1692, Jeoly, the "Painted Prince," was exhibited at the Blew Boar’s Head Inn on Fleet Street, according to several historical records. Newspaper articles from the time specifically mention the Blew Boar’s Head Inn, located near Water Lane (now Whitefriars Road). However, aside from these references, there is no other historical evidence confirming the existence of an inn consistently known by this name. This raises an interesting question: Was "Blew" an old or alternative spelling of "Blue," a temporary variation, or a mistake related to the more famous Boar’s Head Inn?

The use of "Blew" likely reflects the spelling practices of the time. In medieval and early modern English, many words were spelled phonetically and inconsistently. "Blew" was a common spelling for "blue" before language and spelling became more standardized. As time passed, the more consistent form "Blue" gradually replaced "Blew," as spelling rules became more regular and formalized.

Evidence from Newspapers

Cheltenham Chronicle (October 6, 1863)

This article provides a vivid description of Jeoly’s tattoos, which were said to represent "one-quarter of the world" and made from a plant-based dye resistant to damage. The tattoos were claimed to protect against venomous creatures, adding a mystical element to his exhibition. The article confirms that Jeoly was exhibited at the Blew Boar’s Head Inn, with arrangements for private viewings upon request.

Newcastle Chronicle (March 5, 1870)

This article specifically mentions Jeoly’s exhibition at the Blew Boar’s Head Inn, reinforcing the link between the venue and Fleet Street. It highlights Jeoly’s intricate tattoos as a "masterpiece of art and invention," further emphasizing his uniqueness as a public attraction.

Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal (June 2, 1875)

This recounts Jeoly’s story as "Prince Giolo, Son to the King of Moangis or Gilolo," describing his capture during a shipwreck and subsequent arrival in England. The article emphasizes the intricacy of his tattoos and their artistic significance. It specifically mentions his exhibition at the Blew Boar’s Head Inn, located on Fleet Street near Water Lane.

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer (May 27, 1875)

Discusses the broader history of public exhibitions, mentioning Jeoly’s story as an example of how “curious specimens of humanity” were displayed in London. While the specific venue is not reiterated here, the story aligns with the narrative of Jeoly’s exhibition at the Blew Boar’s Head Inn.

Lyttelton Times (November 8, 1912)

Reflecting on historical spectacles, this article recounts the story of "Prince Giolo" as an example of the public fascination with exotic figures in 17th-century England. While it does not specify the venue, the piece aligns with earlier accounts of Jeoly’s tattoos and the mystique surrounding his exhibition.

Theories on the Name "Blew Boar’s Head Inn"

1. A Temporary Name

It’s possible that “Blew” was added temporarily to the Boar’s Head Inn name to make the event sound more extraordinary. In the 17th century, public exhibitions often relied on embellishments to draw crowds, and the colorful descriptor “Blew” might have made the venue seem more exciting and exotic.

2. A Common Spelling Variant

The term “Blew” is a 17th-century variant of “Blue,” often used interchangeably. This suggests that the Blew Boar’s Head Inn may have been the same as the Boar’s Head Inn, with the alternative spelling appearing in promotional materials and subsequent references.

3. A Distinct Venue?

Although no other historical records confirm a separate Blew Boar’s Head Inn, it’s possible that this name was used informally or briefly, specifically for Jeoly’s exhibition. Its location near Water Lane aligns with descriptions of the Boar’s Head Inn, further complicating the mystery.

Was it the Boar’s Head Inn?

If the Blew Boar’s Head Inn was simply an alternate or temporary name for the Boar’s Head Inn, then the venue still exists today as The Tipperary, located at 66 Fleet Street. Rebuilt after the Great Fire of London in 1666, the Boar’s Head Inn was a prominent establishment and an ideal location for a unique exhibition like Jeoly’s. The idea of temporarily rebranding the inn to enhance the appeal of Jeoly’s story fits with the showmanship of the time.

The Exhibition Itself

The handbills and newspaper descriptions vividly described Jeoly’s tattoos, which were said to resist washing and wear. The ink, made from a plant-based dye, was believed to protect against venomous creatures like snakes, scorpions, and other dangerous animals. Such exaggerations were likely added to enhance the mystique surrounding his tattoos, turning them into something almost magical. People were eager to believe in the extraordinary, and this idea of tattoos offering protection from deadly creatures made his exhibition even more alluring.

His "back parts" were said to represent "one-quarter of the world," turning his body into a living artwork. This, too, was probably an exaggeration to further elevate Jeoly’s status as a unique and almost mythical figure. The idea of a body map covering such a vast world was meant to captivate the imagination and suggest hidden knowledge or power.

Jeoly’s exhibition included private viewings, and he would travel by coach or sedan chair to meet his patrons, showing how much London’s elite were drawn to see him in person. The spectacle was more than just tattoos; it was an event where the extraordinary and the mysterious were celebrated.

"Venomous creatures like snakes, scorpions, and other dangerous animals were believed to be repelled by Giolo's mystical tattoos, adding an air of magic and intrigue to his exhibition."

A Lingering Mystery

Despite detailed references to the Blew Boar’s Head Inn, no independent records confirm it as a permanent venue. Was it a temporary renaming of the Boar’s Head Inn, a separate establishment entirely, or simply a miscommunication? The surviving descriptions of Jeoly’s exhibition provide a fascinating glimpse into the culture of spectacle in 17th-century London and leave us with a tantalizing historical puzzle.

References

- Cheltenham Chronicle, October 6, 1863

- Newcastle Chronicle, March 5, 1870

- Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal, June 2, 1875

- Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, May 27, 1875

- Lyttelton Times, November 8, 1912

- The Tipperary Fleet Street - Boars Head

- The Boar’s Head (the original 15th century name of the pub

The Rare Giolo Print by John Savage in the 1816 Towneley Auction

In 1816, an extraordinary auction was held in Covent Garden, featuring the collection of the late John Towneley, a distinguished British antiquarian and art collector. Towneley was known for his impressive collection of prints, drawings, and books, which reflected his deep appreciation for history and the arts. One of the most remarkable pieces listed on page 27 of the catalogue was a print titled “Siamese Ambassador — Indian Princes, and Prince Giolo, son to the King of Moangis,” by John Savage. This print is especially rare, as it captures the Filipino prince Giolo, who was paraded in London in 1692 due to his striking, tattoo-covered body. The print by Savage stands out as a unique glimpse into the fascination with exotic figures during the 17th century.

The auction also offered a diverse range of artworks, from botanical illustrations to naval sketches, reflecting the period’s interest in foreign cultures and royalty. Towneley’s collection was a treasure trove for collectors and art lovers, showcasing some of the most captivating prints and engravings of the time.

By 1816, the print would likely have been considered rare, as many years had passed since Giolo’s public exhibition in London. Such prints would have become increasingly scarce and sought after by collectors. Additionally, prints by artists like John Savage were typically produced in limited quantities, further adding to their rarity. Considering the fascination with exotic individuals in the 17th and 18th centuries, this print would have been a valuable piece for those interested in such subjects, especially in the context of an auction featuring high-quality works from Towneley’s collection.

Listing on page 27 Lot. 358

Catalogue of the John Towneley Auction

The Bindley Granger Auction (1810)

In 1810, another significant auction took place at Sotheby’s, this time featuring the collection of James Bindley, a well-regarded British art collector. Bindley’s collection was known for its rare and valuable British portraits, but one of the most notable pieces was a print of Prince Giolo, created by John Savage.

Prints like this were so rare by 1810 because they were produced in limited numbers, and as the years went by, they became harder to find. The Giolo print, in particular, had already passed a century since its original production, and with fewer copies available, collectors began to place higher value on them.

At the Bindley auction, the Giolo print wasn’t just a portrait of an exotic figure but a rare piece of history—a reflection of the British fascination with people from faraway lands. By the time of the auction, prints like these were considered valuable collectables, especially since they captured a moment in history when the British public was so captivated by the displays of such exotic individuals.

This auction and the Towneley Auction played an important role in preserving these prints and ensuring they were appreciated as rare artefacts. They connected collectors to a unique chapter in British history, where exotic exhibitions and the fascination with foreign cultures were a significant part of public life.

The Bindley Granger. A Catalogue of the Very Valuable Collection of British Portraits, From the Reign of Egbert to the Revolution of 1688.

Listing on page 80 - Lot. 1175.

Bindley Granger British Portraits Auction Catalogue 1810

©Lionel Titchener: Tattoo Club of Great Britain - Oxford