The secret aroma of the tattoo studio

Uncovering the Mystery Behind the Strange Aroma in Tattoo Studios of the 1970s

It was 1972 when I encountered that strange aroma outside a tattoo studio door that got stronger inside the studio. What gave the tattooist this strange atmosphere, the sound of the machines buzzing and that strange smell that sits in the back of the throat?

Of course, some of it was the smell of tobacco as some tattooists were chain smokers, often stopping to roll up another cigarette between tattoos. The customer often had a smoke whilst being tattooed, hence the yellow nicotine stain on the design sheets that built up over the years, but no, there was something else going on.

So in this short article, we begin to explain what was going on and what that great mystery was. Many antiseptic products were discovered and brought onto the market in the early days of tattooing, which tattooists could use. Furthermore, this was the source of that unusual smell in the background.

LYSOL

Many tattooists used Lysol as a disinfectant. Lysol was initially created in 1899 by Gustav Raupenstrauch and was used to help stop the spread of the cholera epidemic in Germany. By the time of the Spanish flu pandemic, Lysol was marketed as a method of cleansing and disinfecting surfaces to combat the spread of the virus. Many tattooists would advertise "antiseptic methods" on their business cards as they had probably read the press about the success of using Lysol.

Tattooists in the 1960s and 70s still used Lysol and green soap in their spray bottles to clean and shave the area before tattooing and used the spray to wipe away any bleeding and pigment as they worked. As a result, the smell of Lysol fills the air.

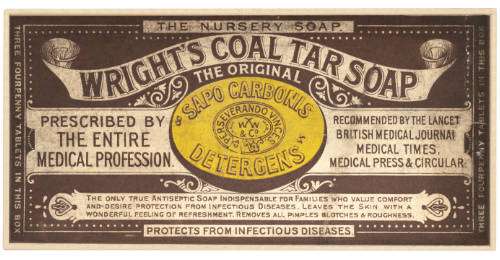

CARBOLIC SOAP

Carbolic soap is a mild antiseptic soap that contains carbolic acid (phenol), derived from either coal tar or petroleum sources, leading to its distinct smell. William Valentine Wright developed the original product in 1860 from coal tar, the liquid by-product of the distillation of coal to make coke. This liquid was made into an antiseptic soap to treat skin diseases. Known as Senior Wright's Traditional Soap or Wright's Coal Tar Soap, and is a famous brand of antiseptic soap that is orange in colour and advertised as an antiseptic soap that would thoroughly clean the skin. Wrights also produced an Alcoholic solution of coal tar that was used in hospitals.

Some travelling tattooists kept a bar of coal tar soap in the travelling trunks. When they opened the box to work, coal tar soap's aroma would fill the room's corner.

Another brand of carbolic soap was Lifebuoy, a red soap introduced by Lever Brothers in 1895. It was initially a carbolic soap that contained phenol. The company added more varieties in the 1950s containing perfume. However, tattooists still used the carbolic type.

PHENOL CRYSTALS

Phenol, also known as carbolic acid, has an unmistakable sweet and tarry odour. Phenol is an antiseptic and disinfectant that has some medical uses. Phenol was one of the first antiseptics used to sterilise medical equipment. Old tattooers used pigment jars with screw-on lids. Some tattooers added a minimal amount of Phenol crystals to the colour pot as a bacteriostatic to prevent the growth of bacteria.

BOILING INDIAN INK

An old trade secret that many tattooists would keep to themselves. Tattooists would boil the ink in a double boiler, a pan of boiling water, with a bowl containing the Indian ink resting in the water. The idea was to boil the ink down to make it blacker. The earlier formula of Indian ink in the glass bottle with the bakelite cap was different back then and would boil down to give a rich black outline and bold shading. The old formula contained phenol, leading to the odour coming from boiling down the ink.

Much of the above would create that strange aroma of an old tattooer working off a battery in a dark corner using various antiseptics in their work. It was not just the sound of the tattoo machine. The soaps and antiseptics used created the whole ambience.

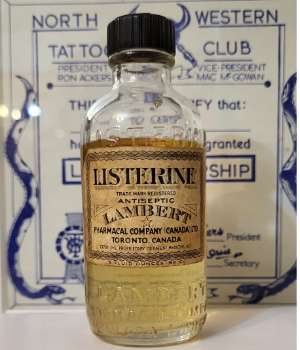

LISTERINE

In 1865, an English doctor Joseph Lister at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Scotland, became the first surgeon to operate inside a chamber sterilised with pulverised antiseptic – a very uncommon practice. Lister had discovered that carbolic acid solution could prevent infection of wounds. What followed was the discovery that Lister's new method would lead to a reduction in mortality rates, and it became more accepted.

News of Lister's method spread and inspired St Louis-based doctor Joseph Lawrence to develop an alcohol-based surgical antiseptic. The formula was a closely guarded secret. It contained menthol, methyl salicylate, eucalyptol, and thymol. Dr Lawrence named his new antiseptic LISTERINE in honour of Dr Lister's earlier work in developing medical antiseptics. Dr Lawrence hoped he could promote Listerine as a general surgical antiseptic for cleaning cuts, scrapes and other wounds. In 1881 the formula was licensed to a local pharmacist named Jordan Wheat Lambert, who formed the Lambert Pharmacal Company to market Listerine. By 1895 Listerine was being promoted as an antiseptic mouthwash to dentists.

Many tattooists would buy powdered pigment to make up their colour pots, and the pigment mixed with Listerine and a few drops of Glycerine. Then, tattooists would use Listerine in spray bottles to clean the arm as they did the tattoo.

ROCCAL

Rocca antiseptic was a soapy blue liquid used by tattooists to wash the skin before shaving and tattooing. It was a similar bottle to Listerine and had a soft soapy medical smell.

WITCH HAZEL

Some tattooists would mix their pigments with witch hazel and use it to wipe down the finished tattoo.

ROSE WATER (Rosaceae)

Some tattooists used rose water to mix their pigments. The invention of rosewater, credited to Avicenna, a 10th-century Persian scientist, had spread to Europe by the Middle Ages. Beyond the perfume trade, rose water has powerful antiseptic and antibacterial properties that can prevent infection. In addition, rose water help wounds heal faster due to its antiseptic and antibacterial properties, and it has also been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect.

TCP

Bill Skuse in Aldershot kept a small milk bottle full of TCP on his counter, which he would use to wipe the skin with TCP before tattooing. Then, finally, he would wipe the area with a TCP-soaked cotton ball. Lionel Titchener of Oxford would take off the air intake grill at the bottom of the air conditioner in the studio and place a small tray with cotton buds soaked in TCP inside. The whole studio and waiting room would smell of TCP.

OTHER SOLUTIONS

Other solutions used in the tattoo studio with a less pungent odour were Hibitaine, discovered in the 1950s. Surgical spirit or rubbing alcohol. Rubbing alcohol is either isopropyl alcohol or ethyl alcohol mixed with water. The application of surgical spirit is to disinfect minor cuts and to sterilise and harden the skin. In addition, surgical spirit works against bacteria, viruses and fungi.

Methylated spirit. The difference between methylated spirit and surgical spirit is that methylated spirit is used mainly for removing stains and as a fuel in small lamps and heaters. In contrast, the surgical spirit was used as a disinfectant to prevent bedsores and harden the skin of the feet. Both methylated spirits and surgical spirits have nearly similar chemical compositions, used in different applications. For example, old-time tattooists sometimes used methylated spirits to clean the skin before applying for transfer.

FERRIC CHLORIDE

Some old-time tattooists used this to wipe the finished tattoo to stop bleeding. For example, tattooists Ben Gunn and Cash Cooper used Ferric Chloride on the finished tattoo to stop the bleeding.

IODINE PENCIL

George Burchett mentions using Iodine pencils to outline the tattoo on the skin. (Memoirs of a Tattooist)

ETHYL CHLORIDE

George Burchett would use it as an anaesthetic to "freeze" the skin.

OZONE

Some old tattoo machines were not fitted with capacitors, so you had a blue spark between the contact screw and front spring—this arcing caused ozone formation. Ozone gas is often present in the vicinity of electrical arcing. It has a very distinctive smell and odour similar to chlorine. That's why its name was derived from the Greek word ozein, which means "to smell".

With no capacitors, the front spring was often burnt and corroded, leading to more electrical resistance, so tattooists would turn up the voltage and get an even bigger spark. Some tattooists would have a clip cord straight from a car battery, with no foot switch to the tattoo machine, opening up the contact gap to control the speed.

We’d love to hear your stories and insights! Did any of these old-school aromas or techniques bring back memories or remind you of your own time in the studio? Perhaps you recall the sharp, antiseptic scent of Listerine or the earthy tang of coal tar soap lingering in the air as you worked. Did this bring back memories of your first visit to a tattoo studio? Did you ever use any of these classic products or have other unique practices that shaped your experience?

For those who’ve been in the game for a while, what are your thoughts on how these smells and methods contributed to the atmosphere and tradition of tattooing? And for newer artists, do any of these vintage techniques feel like an entirely different world, or do they spark an interest in exploring the roots of the craft?

This article is not all-inclusive. We would be pleased to hear any additional information.

Take a moment to share your thoughts below. Whether you’ve got a story, a question, or a reflection, we’re excited to start a conversation that honors the rich history and unique experiences in tattooing.

©Lionel Titchener: Tattoo Club of Great Britain - Oxford