From Vintage Stencils to Thermal Transfers

100 Years of tattoo transfer paper making.

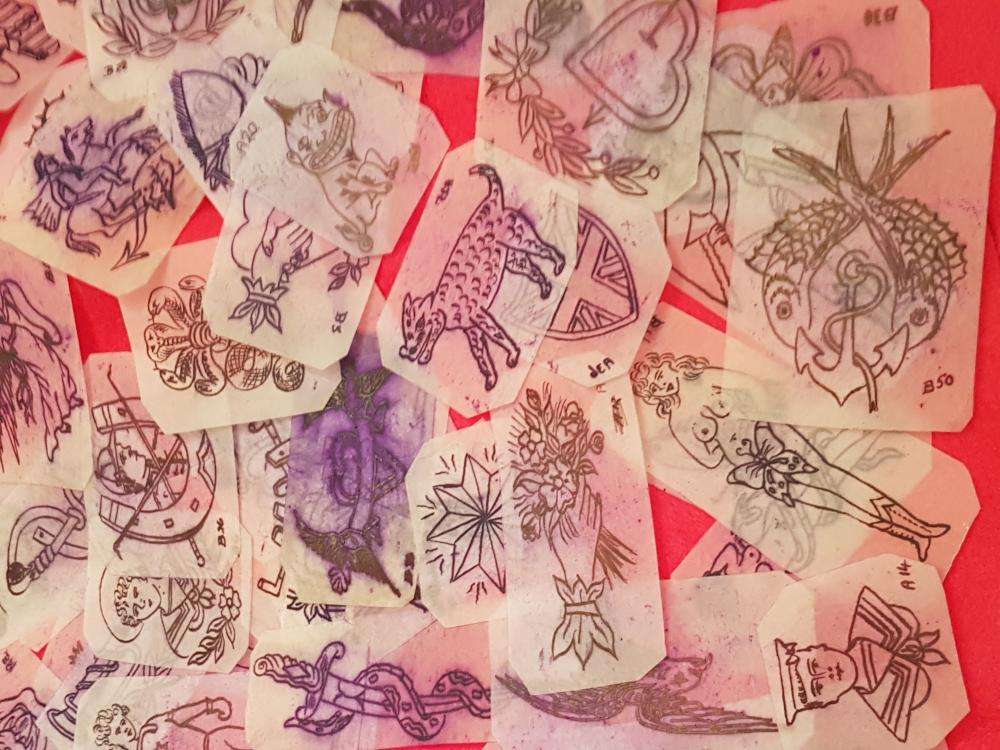

Edwardian tattoo supply companies, such as Charles Burchett Davis, amongst others, sold tattoo kits along with hectographic tattoo transfer paper to place an outline of the tattoo onto the skin. These tattoo transfers are made with thin tracing paper that would mould to the body's shape when applied. Some tattooers would use shiny toilet paper, one brand being Izal, similar to tracing paper. It was found in schools, offices, and government buildings. Izal toilet paper was impregnated with carbolic acid disinfectant giving it a distinctive smell. Also used on the railway, these sheets had the name of the rail company printed on them.

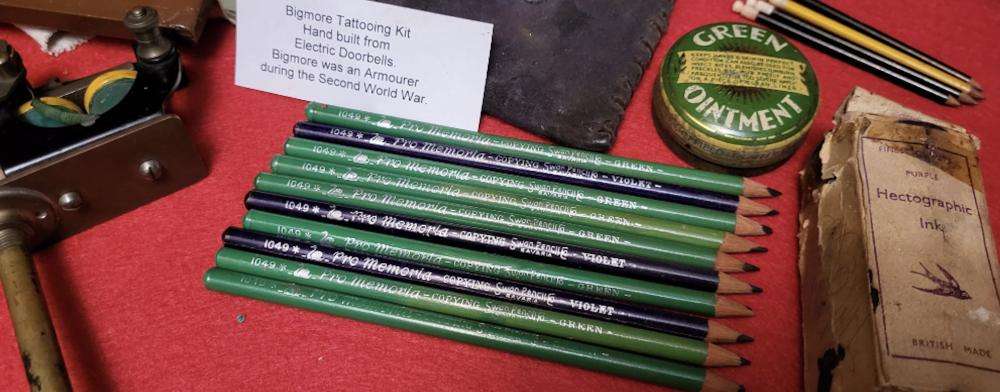

The tattoo design is drawn on the tracing paper, and on the reverse, the outline was carefully followed using a fine mapping pen and hectographic ink. The transfer was then left to dry overnight. The result was a slightly raised, shiny line of ink. When used, the area to be tattooed was first washed with soapy water and shaved. Next, a light smear of Puritan olive oil-based soap was applied to the skin to make the surface tacky. The transfer is then placed on the skin's surface and lightly rubbed to leave a line. It was important not to wet the skin too much as the transfer lines would smear and spread. Some tattooists preferred Wright's Coal Tar soap due to its antiseptic properties. This soap also had a unique odour. Later, tattooists would use Dettol to clean and dampen the skin before applying the hectographic transfer. Dettol, invented in 1933, was used by doctors and midwives in hospitals to disinfect before delivering babies. Dettol gave a better transfer than the old olive oil-based soaps.

This method made long-lasting transfers that did not wear off during the tattooing process. There was, however, a downside to using hectographs ink. When making the transfers, it is crucial not to get the ink on the fingers; otherwise, later, when looking into the mirror, there would be purple smears from rubbing and scratching the face whilst making the transfers. In addition, hectographic ink was difficult to remove from the skin. It would get on door knobs, bannister rails, and everything that is touched by not taking care when making the transfers.

In the United States, there is a different method of making tattoo transfers, the acetate stencil. First, the outline is carefully engraved by hand into the acetate surface with a gramophone needle held in a pin vice. Next, powdered charcoal was dusted over the acetate and carefully wiped away, leaving charcoal dust in the scratched line. Next, the skin was shaved, and a thin coating of Vaseline was applied. Then, the acetate was carefully placed on the skin, leaving the outline sticking to the Vaseline. Unfortunately, this also had a downside. The stencil outline was delicate and easily wiped off. One tattooist who used acetate stencils in the UK was Dennis Cockell from London.

Another disadvantage of both these methods was the time it took to make a stencil. However, they were fine for off-the-wall designs. Each design on display is numbered, and the stencils are stored ready for use in numbered envelopes.

One way to make a quick transfer was to use a hectographic copying pencil. These pencils, introduced in the 1870s, were used in letterpress printing. They did not have an eraser on the end. The core was graphite or clay mixed with aniline dyes, and a popular colour for tattoo transfers was methyl violet, a purple. The dye content varied between 25 per cent and 50 per cent, which most likely explains why some tattooists complained that they did not make a good transfer.

Another method for tattoo transfers was hectographic carbon paper, which was used to make master sheets for duplicate machines. The tattoo design was first traced onto thin tracing paper. Next, the tracing paper was placed on a sheet of hectographic carbon paper ink side up and put on a hard surface like glass. The design was then traced with a fine ballpoint pen, which left a line of hectographic ink on the back of the tracing paper. Hectographic carbon paper was available at all good stationary shops until the 1970s, when it became hard to find as the desktop photocopy machines appeared in offices, replacing duplicating machines.

It was a tattooist in the United States who, in the 1970s, discovered a new and quicker method of making tattoo transfers, Lou Robbins, owner of the Mad Hatters Tattoo Studio, Old Orchard Beach, Maine. He found 3M Thermo-Fax machine stencils could be used on the skin. Lou bought six Thermo-Fax machines. He kept one for himself and sold five to other tattooists. Here in the UK, these transfer machines were costly. In 1985, they were just over £600.

Thermo-Fax is a trademark of 3M and was introduced in the 1950s. The spirit masters made the master copy in spirit duplicating machines, a precursor to the modern photocopier. Before that, wax master sheets were used. The company eventually dropped 3M Thermo-Fax machines as sales fell due to the invention of the office photocopier and laser printers that replaced duplicating machines. Yet tattoo artists continued to purchase 3M machines when and where they could locate one on the secondhand market.

It is unknown when 3M machines were first discovered to make tattoo transfers. Still, Lou Robbins was the first tattooist to recognise their usefulness in the tattoo studio and pass the information on to other tattooists. Since the mid-1970s, spirit transfer papers have been used to make tattoo transfers.

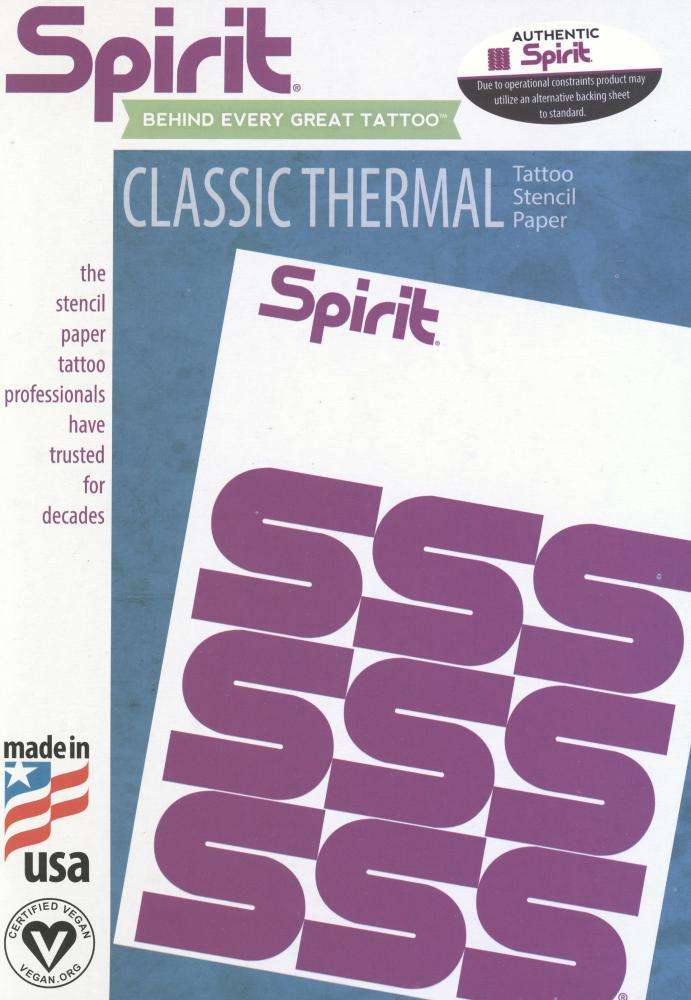

Due to the popularity of thermal stencil machines being used by tattooists, one company that for generations made the thermal sheets used in the Thermo-Fax transfer machines set about formulating a new stencil paper specifically for tattooing, and this is how it began.

Spirit Thermal Tattoo Stencil paper is made by Colonial Converting Company, a family business founded by Earl Bradley in 1948, producing carbon paper and typewriter ribbons. Then in the 1960s, the company started manufacturing transfer paper for duplication machines.

With the advent of photocopying and laser printers using toner, demand for transfer paper use in duplicating machines began to fall. Nevertheless, tattooists were still buying the S-branded boxes of Reprofax transfer paper. It had been discovered that, like hectographic carbon sheets, these transfer sheets could be used for tattoo transfers.

The S brand Spirit box appeared in the 1970s. Colonial continued to manufacture transfer paper for tattooists, Reprofax became ReproFx, and the S logo is still on the modern packaging. All are manufactured in the United States. Colonial began selling directly to the tattooing industry in the 1990s.

https://www.tattoo.co.uk/blog/post/tattoo-history/history-of-vintage-tattoo-transfers

https://www.tattoo.co.uk/blog/post/tattoo-history/history-of-vintage-tattoo-transfers

Colonial Converting Company continues to produce the highest quality tattoo transfer paper. Packaging was changed again in 2008, but it still includes the original S box within its design. In addition, they use high-visibility purple dyes designed to give a robust and long-lasting transfer, with a specially formulated transfer cream using cosmetic-grade ingredients.

Looking Back: Tattoo Transfers Through the Ages

Tattooing has always been a mix of artistry and ingenuity, and nowhere is that more evident than in the evolution of tattoo transfers. From hectographic ink to the distinct hum of a Thermo-Fax machine, each step tells a story of tattooing’s resourceful past.

Do you remember carefully tracing designs onto hectographic paper or the challenge of getting the perfect transfer with acetate stencils? Maybe the smell of Wright’s Coal Tar soap or the distinct purple stains of hectographic ink bring back memories of long hours spent perfecting your craft.

For those who worked in the early days, we’d love to hear your stories. How did these tools shape your approach to tattooing? Were there any tricks or materials you swore by that others might not know? And for anyone who remembers scouring for Reprofax transfer sheets or working with vintage Thermo-Fax machines, your experiences are treasures from a time when tattooing relied on creativity and determination.

For the newer artists, what do you think when you hear about these older techniques? Do they feel like a lost art, or do they inspire you to explore the roots of tattooing?

We’d love to hear your memories and insights in the comments. Whether you’re an experienced tattooist with stories of the old-school days or a newer artist curious about the past, your thoughts can help illuminate the path from the past to the present. What techniques do you remember using? Do any of these stories resonate with your journey as a tattoo artist? Drop a comment below and join the conversation!

History of Vintage Tattoo Transfers

©Lionel Titchener: Tattoo Club of Great Britain - Oxford